The Language of Your Soul: A Christian in Modernity

John Donne Arriving in Heaven, Stanley Spencer 1911

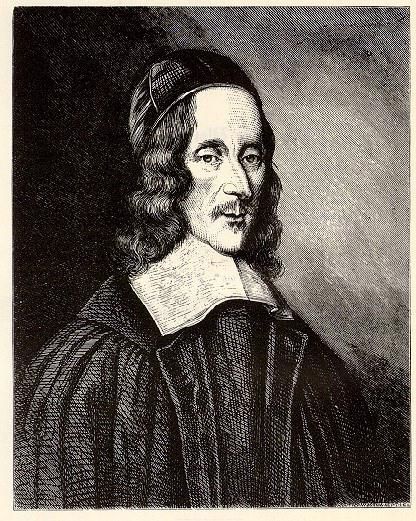

“When one man dies, one chapter is not torn out of the book, but translated into a better language; and every chapter must be so translated; God employs several translators; some pieces are translated by age, some by sickness, some by war, some by justice; but God's hand is in every translation, and his hand shall bind up all our scattered leaves again, for that library where every book shall lie open to one another;”

John Donne, Devotions

Translating is typically seen as a useful tool to gain understanding. For the most proficient translator, the process is seamless; which, this is a great kindness. It is quite an act to take one language and alter the words, tone, and inflection (but not meaning) for the benefit of others.

But if we only consider the before and after, then we’ve missed a grand step altogether—death.

One version has to die so that another can live. Fyodor Dostoyevsky wrote Crime and Punishment in Russian in 1886, with its first English translation in 1911. That Russian version had to die to all those at the turn of the twentieth century who did not speak the language, and likewise to me when I first read it years ago. But the death of Dostoyevsky’s version brought life to an entire population of the world that might have been left in darkness.

Christian parallels

And yes, as Christians we can see the marvelous parallels here with the believer’s life and life everlasting. I love the lines Donne draws in maintaining an eternal perspective rather than death receiving an equal portion. There is no resting point in translating; meaning, there are not three stages: Russian to unnamed middle step to English. It’s just: Russian to English. When one language passes to another, it is in one motion.

The same is true upon death: life to everlasting life. In not attempting to oversimplify or callously handle the process of death, what I mean is this—death itself is not a layover for everlasting life. This of course still leaves plenty of space for complex, hard emotions surrounding death. Age, sickness, war, and justice are just a few Donne gives airtime to, and none of these are simple or tidy. In the same chapter Donne—on his own sick/death bed with the bubonic plague of the seventeenth century—asks God why so many miseries must be endured before we reach glory.

But what a great comfort to know that a Christian’s death means translating life into real clarity of who we were made to be and what we were made to do: glorify the Lord forever.

We have bad taste

But does it matter what we are being translated from? In other words—life between salvation and death: Does the language of our soul matter? We know that when we become Christians, we are “new creations” (2 Corinthians 5:17). We know that “the one who endures to the end will be saved” (Matthew 24:13–14). We know that we aren’t to “be conformed to this world but be transformed by the renewal of the mind” (Romans 12:2). Endurance, transformation, and renewal are encouraging but steep orders, and we have all witnessed a myriad of their applications.

For the modern American man the original language looks differently than it did from the first century church or our Puritan brothers and sisters. Early Christians like Polycarp and Blandina endured harsh persecution. Living in a more primitive time, their distractions may have been light but abuse was heavy.

And modern life? For my own context, the scale nearly topples obversely. As an American in the 21st century, I have it all, yet the echoes from the mirror, ads, and media brand a contrary narrative. The curtain pulled back, we know the design is addiction, yet the resistance still wanes as so many drift along in the haze of busyness, boredom, and self-amusement.

What I’m getting at is this—we naturally have bad taste. We have propensities and preferences not aligned with Scripture, affecting the language on this side of that ultimate translation to everlasting life. Even as mature adults, reckless habits, even unseemingly at first, can form one degree of heat at a time.

Our original language

What we as Christians do with our souls before the death of the body certainly does matter. In 2 Peter 1:3–11 God has “granted to us all things that pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of him.” Verse 10 says, “Therefore, brothers, be all the more diligent to confirm your calling and election, for if you practice these qualities you will never fall.” These qualities are outlined in 5–7: faith, virtue, knowledge, self-control, steadfastness, godliness, brotherly affection, love. We don’t have to be overtly perceptive to note the different trajectory 2024 and beyond is headed, especially in terms of technology and entertainment.

Most aspects of modernity are tools, and, therefore, have no moral value. Being conscious, reflective, and honest of how and when we wield them (which is where morality does come into focus) is crucial in this Christian life because, again, the original language matters.

When we think about what God has granted to us, are we acknowledging any of it? He does not give us stones but real bread. He does not give us snakes and scorpions but abundant life (John 10), confidence (Hebrews 10), and peace (Philippians 4). He grants us His presence. Yes—even in a tumultuously dark, American context, we have been given life and godliness.

What sort of personal culpability are we aligning with? The list from 2 Peter 1:10 looks and smells of abundant living while the fast-paced production and accessible novelties we carry around smell of. . . vanity? Futility?

The language of your soul

The modern man’s life language does not have to be worthless. There is hope. While we cannot affect advancements or trends much, we can certainly choose how we respond to them. And this is what our original language is made up of: small, daily, consistent choices about our surroundings that shape and provide our material for conversations, emotions for handling change, and private narratives we hear on repeat.

I think we all must be honest about the orientation of our own trends. If you were to maintain your current time outlay, food and drink patterns, conversation topics, and entertainment standards—what would life look like in one year? Five?

One posture Christians must repeatedly return to is aligning and re-aligning ourselves with God’s taste. What does He call beautiful? What does He deem praiseworthy? Instead of letting modern culture railroad us or even find ourselves submitting to its pace and trajectory, let our souls learn a holy language from the Creator of virtue. Let us set up our lives to experience God’s beauty through nature, people, prose, prayer, or even a simple silence.

Worshiper, wife, mom—with the help of the Lord, this is my hierarchy of work. Beyond this I homeschool the girls and hold down a staff position at Zionsville Fellowship in Zionsville, Indiana. I read, write, do yoga, cook, and practice thinking pure and lovely things.